Organizing the Discussion Area

The discussion board (whether the main board or including the student group boards) is often the heart of an online course as far as student dynamics is concerned, providing a home base for conducting the formal week to week activities of the course, asking and answering questions of clarification, and offering a main venue for collaboration and interaction of all sorts. Interaction takes place between students as well as between instructor and students. All of these activities must be planned in advance as part of your design of the discussion area. In the Preparation for Teaching Online (PTO) workshop, we discussed the differences between using blog or wiki areas for discussion and using Blackboard discussion boards. Please refer to the Week 2 materials of the PTO workshop for that information as well as on the topic of discussion facilitation. We will repeat only a few pertinent points here.

One should generally include three forums that apply to the course as a whole:

- An introductions forum—a standalone forum used during the first week of the course that is easy for students to return to whenever they want to familiarize themselves with details about a classmate. This assists in building community for a class.

- A discussion forum established for Q&A about the course, monitored by the instructor. This is where students can post questions that may not be directly related to a discussion topic of the week. For example, questions about assignments and requirements of the course, how to perform a task, to report a broken hyperlink, etc.

- A casual, ungraded discussion forum for off-topic and informal conversations, named appropriately for your course (e.g., Cyber Café). Some instructors will also post in this area, although it is mainly intended for students.

In the Preparation for Teaching Online workshop, we discussed the different user options for instructors and students available in Blackboard discussion boards and the implications each option has for what you and your students can do and how discussion activity or sharing within a forum is carried out.

What’s the Purpose of Your Discussion Activity?

To prepare for your use of asynchronous discussion opportunities, you should first decide how you want to use discussion in relation to your presentation and assignment elements in the course. In other words, decide whether discussion topics will closely follow the questions you raise in your lectures and other presentations, or whether the topics will provide opportunities to introduce additional materials and further applications of ideas you’ve presented. Discussions that are coordinated with assignments and assessments must be scheduled to allow enough time for reflection and response. If student assignments are presented in the online classroom and students are asked to comment on them, guidelines and procedures must be set up in advance to make sure that the discussion is structured and focused. Naming conventions are important to avoid confusion—for example, do you want students to include the title of their project in their threads? Do you want projects posted by means of an attached document?

Remember that a forum may be the setting for more than a pure discussion. It can be a place to demonstrate problem solving, share assignments, stage debates, post group projects, and serve many other purposes. If you teach a hybrid course, you will need to closely coordinate the online discussion fora with your f2f meetings. The discussion can be used as a place to post questions before a f2f meeting, to post full projects which can only be presented in short form within the time limit of a f2f meeting, or to continue a discussion begun in a f2f meeting. In regard to grading participation you may want to give combined scores for discussion participation that occurs in either online or f2f mode, or to give scores only for online participation. You’ll also have to decide who will lead particular discussions–you, the instructor; a teaching assistant; or a student or group of students appointed for this purpose each week? What guidelines will you use for teaching assistant or student facilitated discussions? Facilitating a discussion is hard enough for an experienced instructor. If you think students are at the appropriate level of development to facilitate a discussion, then it is best to provide some guidelines for doing so.

Tips for Setting Up Discussion

-

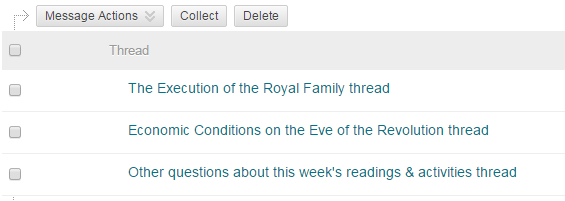

It’s a good idea for the instructor to start all major topic threads unless you have designated a forum for student presentation or have designated students to act as the moderator. If appropriate for the particular forum, you can ask students to start new threads. And, if you wish to, you can allow students to contribute additional threads. This arrangement should be considered with great care, however, because students often tend to create new topics without real necessity, and your discussion area may soon be overwhelmed with too many threads on duplicate topics. Below, an example of topic threads started by a history instructor:

-

Narrow down topics. A good discussion needs pruning and shaping. An overly broad topic thread–say, “The French Revolution: What Do You Think of It?”–will often result in very fragmented discussion. This is especially true in an introductory class, in which most students know little about the subject. If you divide up broad topics into logical subtopics–say, “Economic Conditions on the Eve of the Revolution” or “The Execution of the Royal Family”–you can prevent the discussion from going off in too many directions.

-

Provide scaffolded techniques as appropriate. For example, in an introductory course, a discussion based on specific readings in the textbook, on a focused web site visit, or on assigned exercises, coupled with your guideline questions, will likely be more productive of a fruitful discussion than simply pointing students to the forum and expecting them to find their own direction. A short series of closely related questions can allow students to jump in on any one of the points and still find themselves “on topic.” In our example of the French Revolution, a topic thread might contain several questions about the economic conditions and invite students to choose one to which to respond: “Please address one of the following: What were the land-holding patterns? How important was foreign trade? Had the average wellbeing of the citizens improved or worsened in the years leading up to the Revolution? Give a rationale and provide support for your response.”

-

Organize forums and threads to reflect the class chronology or topical sequence and suggest a pattern for posting. The organization of discussion forums should complement the class structure but also provide some reminders of the course chronology and sequence. For example, creating one for each week or unit of the course helps students know at a glance where they should be looking for that week’s activity. There should generally be a forum available for each week or unit of the course unless you want students to post questions related to weekly course content to the general Q&A forum. Suggest a schedule for posting that is appropriate to the topic, assignment, and your student audience—for example, if you want students to comment on other students’ postings, you might suggest that everyone post their first responses to your question by midweek and to classmates during the remainder of the week. You may even set up your system of credit for the discussion participation rubric to reflect that.

-

Create thread topics so that they correspond to and support appropriate and relevant activities. Tying your thread topics to the assignments, readings, projects, and exercises for a particular week will help keep students on topic in their discussions and also provide an obvious place to discuss anything that occurs in the course during that week. While you may have some key topics in mind, do allow students to ask related questions that you may not have anticipated. Adding a prompt at the end of the discussion question such as “If you have another question based on this week’s reading, feel free to post it in reply/post it in a new thread.” Or you may create a thread each week that is a placeholder for “other questions about this week’s readings and activities.”

For some additional tips about constructing good discussion prompts, see this 4.5 minute video by Galina Culpechina, “Effective Discussion Prompts for Online Discussion Board”:

Tips on Constructing a Good Discussion

When your forum is designed to support a discussion or debate, how can you construct discussion questions or prompts that will elicit appropriate responses and ensure that dialogue takes place among students, not just closed responses? Here are some strategies for constructing discussion—depending on your subject and course content, as well as the level of proficiency of students, one or the other might be most appropriate:

- Work backwards from a learning outcome that you want to accomplish in part by means of a particular discussion. Locate that outcome on Bloom’s Taxonomy and construct your discussion prompt using appropriate verbs corresponding to the desired level.

- Discussion questions that have only one answer belong in a multiple choice test, not discussion.

- Questions that are fact-based (“Who lies buried in Grant’s Tomb?”) or only opinion-based (“Do you like chocolate?”) are likely to lead to anything but a single response from each student. Use more open-ended questions and those that are higher on the Bloom’s Taxonomy scale.

- Don’t ask loaded questions such as “Do you think people should be able to get away with murder?” or “Isn’t technology destroying our civilization?”

- Ask students to provide a reason or foundation for their response—based on text, experience, or observations, as is appropriate to the subject.

- Ask students to reflect on a question in terms of real-world experience or in response to an example.

- Ask students to provide a critique based on a rubric or set of criteria.

- Provide for an extended discussion through a debate or role-playing strategy, case study, scenario or game which requires different steps—perhaps research, paired or small group discussion, and a final presentation. Such discussions can be a series of discussions or steps leading to or after a discussion.

- Stimulate interest by building a discussion around a resource or media object or ask students to find and bring back something in order to take part in the discussion.

- Provide feedback to student moderators on their discussion questions before questions are posed. Give student moderators examples and guidelines for constructing good prompts.

- When appropriate, give students some choice in which question to answer.

- Make sure the discussion question is clearly understood—when helpful, refer to assigned readings or resources that provide the basis for the discussion question.

- At the end of a course, review the reaction to discussion questions and note those questions which did not lead to effective discussion. Revise those accordingly.

The importance of a good participation rubric and expectations

A participation rubric and clear criteria for both quality and quantity of participation are important factors in a successful discussion. Always include a realistic requirement for students to comment on or respond to classmates. However, asking students to respond to more than one or two classmates in a week can result in superficial responses. Providing examples of good responses rather than just stating criteria can be particularly helpful in introductory courses. Be prepared to explain what you mean by “substantive” or “responsive” when those are your criteria for responses. See Module 6 on rubrics for more information on constructing rubrics to both guide and assess student discussion.

References

Some of this material has been adapted from Ko, S. S., & Rossen, S. (2010). Teaching online: A practical guide (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

[…] 12. Constructing Effective Online Discussions – Course Design … […]

[…] 11. Constructing Effective Online Discussions – Course Design … […]