There are some issues related to the creation of content for an online course that may not readily come to mind when faculty begin developing online course materials. Some of these are readability of text, pacing, and accessibility. All of these should be considered early on in the design of a course to avoid having to make time-consuming revisions at a later stage in the development of a course.

Readability

How easy is it for your students to understand your lectures, commentary, or readings? The difficulty or ease with which a reader can comprehend a text is referred to as its “readability.” Many faculty have a finely-attuned sense of when the text is pitched to an appropriate audience, but our expertise can also lead us to misjudge the level at which we present content. For example, if we are used to writing for a scholarly audience, we may need to rethink our presentation to undergraduate students in an introductory course.

Readability tests can be used to estimate or provide a rough determination of the reading level needed to understand a passage of text, whether of the content you create or the texts you assign. While some tests format their results in the form of a scale (say from 1 to 100), most translate this information into an estimated grade level. While readability tests are not intended to replace careful editing and revision, they can serve as an alert or warning. You might want to put a new lecture or explanation through a readability test or if you are revising commentary written for one audience to use for a rather different audience, a readability test might be helpful to you. In considering whether to use a readability test, do not make the assumption that creating a more easily understood text means somehow “dumbing down” your content.

A high grade level or difficult readability score may be a sign that your writing is too complex for your audience. However, it is important to remember that a low score does not necessarily mean a passage will be easy for your students to understand. For example, a student’s lack of familiarity with a particular genre or type of language common to a discipline may struggle to understand what is otherwise a straightforward text. Also, because the tests consider form and not content, your writing could produce a low score but still be filled with terminology that is unfamiliar to your students. So audience analysis is still very important to consider—who are the readers in your class and what sort of preparation can they be assumed to bring to this content? Do you need to change your language, or is it just a question of providing more context or supporting materials?

Make sure to keep the following in mind whenever you use a readability test:

- Are the ideas (and not just the sentences) in this passage complex?

- Do the sentences make sense? Remember: the readability tests do not take content into account. A nonsensical passage could be scored as highly readable.

- Is the passage or sentences organized logically?

- Is the passage appropriate in regard to other factors you may know about your student audience?

The Top 3 Readability Tests

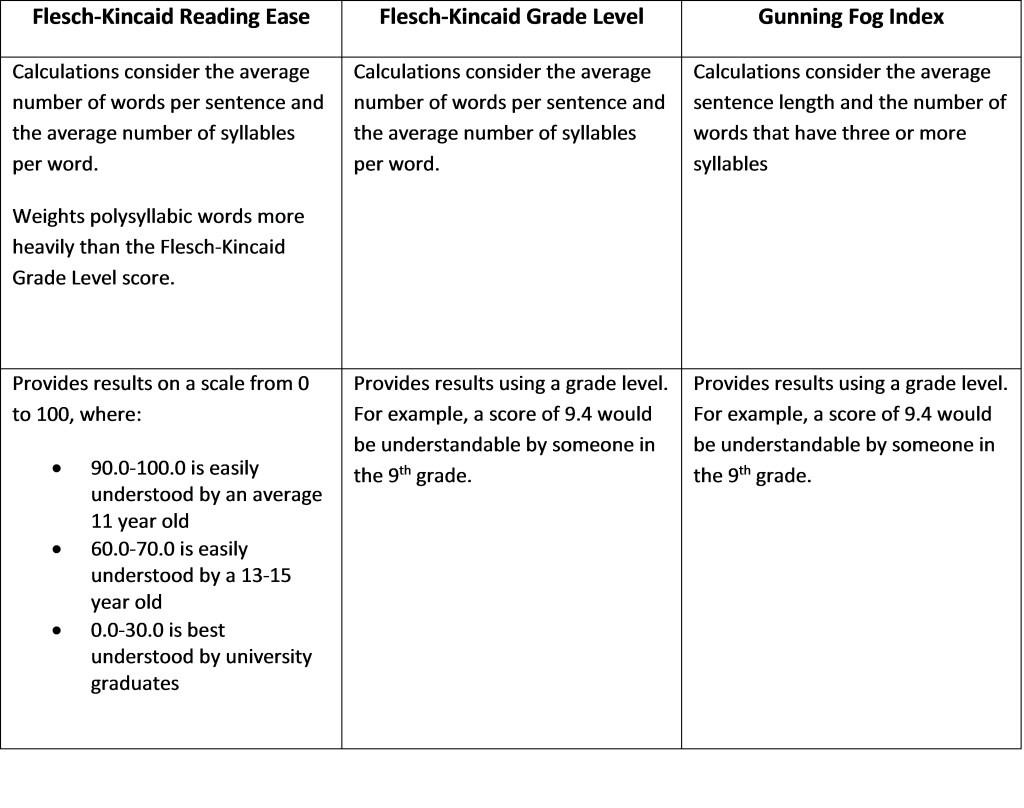

The most popular readability tests are the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease, Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, and the Gunning Fog Index. Here is how they compare:

Microsoft Word can be used to check a document’s readability using the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level scores:

- To turn on this option on a PC: Click File and go to Options>Proofing. In the “When correcting spelling and grammar in Word” section, check boxes for “Check grammar with spelling” and “Show Readability Statistics.”

- To turn on this option on a Mac: Click Word>Preferences. Under “Authoring and Proofing Tools,” click “Spelling and Grammar.” In the “Grammar” section, check boxes for “Check grammar with spelling” and “Show Readability Statistics.”

While the above three formulas are the most popular, there are several tests that are also used fairly often. These include:

- The FORECAST Formula: Best used for: documents that do not contain complete sentences, such as some exams, bulleted lists, and technical instructions.

- SMOG (Simple Measure of Gobbledygook): Best used for: when you want to know the grade level at which someone would have 100% comprehension of a passage.

- Kane: Best used for: Mathematical English. Developed by Robert B. Kane (“The Readability of Mathematical English,” published in the Journal of Science Teaching 5.3 [1967]). This scale requires 400 word and/or math tokens in order to formulate the readability of a passage.

Online Readability Test Tools

While Microsoft Word can provide the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease and Grading Level scores, there are also online resources that can provide this information and more. Here are examples of the web tools that are out there:

- Readability-Score.com A website that will compute the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease score as well as five grade level calculations including Flesch-Kincaid and Gunning Fog. Also provides text statistics, such as sentence count, average syllables per word, and average words per sentence. This tool is only accurate for passages written in English.

Pacing

As mentioned in the Preparation for Teaching Online workshop, be careful not to overload your course with more work than would be assigned in a traditional face-to-face course. This is sometimes done out of a lack of confidence in the online medium itself. But realize this—your textbook assignment is still the same, but in addition to whatever text or online articles, publisher materials, or other main resources assigned, students will also have to take time to access the Blackboard classroom, locate and read announcements, read discussion postings, etc. And they will still work offline to complete some of the assignments–if they have a group project, it may take them considerable time to just get organized. So all this means additional reading and “click time.”

Everything takes longer online–an odd fact when we consider that people often tend to focus on the convenience factor in online education. A brainstorming session that might take one hour in a face-to-face class meeting or a synchronous online session will likely need two days to accomplish if done asynchronously.

Pacing of an activity that takes place online in an asynchronous environment is different than one conducted face to face. Communications need time for the back and forth of students who are logging in at different intervals. This is especially true for small group work that takes place online–the group will take longer to reach consensus on any point if they are doing so on an asynchronous schedule, with each group member logging in at different times. As suggested in the Preparation workshop, if you are not sure about the pacing of an activity, ask an experienced online instructor to review it or, if possible, try going through the steps or a portion of the assignment yourself, then factor in the additional time that someone less experienced than yourself would likely take to complete it.

Pacing can also be affected by a lack of scaffolding for a complex assignment. Some assignments might benefit from being broken down into several parts, with feedback loops in between these stages, and additional resources, guiding rubrics, or examples to support students in the tasks involved.

Finally, pacing for a hybrid class requires careful calculation of the time involved when student work in one mode is dependent on completion of tasks undertaken in the other mode. Also, the total time for students to complete their work in both the face to face meetings and online needs to be considered to avoid the mushrooming of the class into a burdensome “ class and one-half.”

Accessibility and Universal Design

What is Accessibility and Universal Design?

-

Accessibility in online education refers to an inclusive design concept in which all students can perceive, understand, navigate, interact, and contribute to their web-based courses.

-

Universal Design refers to the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design (Kearns et. al. 2).

Universal design can improve the overall quality of courses at SPS with lectures, discussions, visual aids, videos, printed materials, labs and fieldwork that are accessible to all students. Accessibility and Universal Design not only benefit students with intellectual and physical disabilities, but also accommodates different learning styles and can help mitigate technological problems by providing course content in several formats. In general, students who rely on screen readers to access course sites and materials face the greatest obstacle to online education, and while these students may comprise only a small number of our population here at SPS, designing your course to accommodate them actually makes your materials more easily read by everyone, and will help you avoid having to redesign in the event you do have a student who requires accommodation. Among the groups of students who benefit from universal design are students for whom English is not their primary language, visual or auditory learners, and students with health impairments, among others. It’s best to build accessibility into your course from the beginning instead of trying to add it in the end; this guide will give you a quick overview of accessibility practices.

What steps can you take to ensure that your course site and course materials are accessible to all?

Best Practices for Accessibility

- Generally, simple is best.

- In all your documents as well as when writing in Blackboard, important information should not be emphasized with color alone. For example, don’t say “Assignments in green are due on Wednesday and assignments in red are due on Friday.”

- Use clear 12 pt (or larger) font. For example: Arial, Times New Roman, Helvetica, or Verdana.

- “Chunk” information into organized themes with clear headings.

- Avoid using text boxes where possible.

- Use text to provide a clear description of website links rather than just the URL. For example, when creating a hyperlink use text display to name the website rather than simply providing the URL or saying “Click here.”

- Provide descriptive text for all non-decorative images. This text, also known as “Alt Text,” allows screen readers to provide visually impaired students with a description of these features.

- When creating lists, use ordered lists so that items are numbered.

- Eliminate flashing/ blinking content in all materials and use animations/ transitions in PowerPoint only when necessary.

- Use the Tab Key rather than the Space Bar when indenting or spacing.

- Use “Styles” for consistency. (Styles are a predefined combination of font style, color, and size that can be applied to selected text in order to identify headings and subheadings in your document and make it more legible to screen readers.)

- Use simple tables and designate header rows. For example, do not merge cells, split cells, or embed tables within tables/ cells.

- In Powerpoint: use templates, avoid creating text boxes, and give each slide a unique title.

- Use the Accessibility Checker to check for other accessibility issues in Word, and in Acrobat Pro for PDF documents.

- Start with accessible Word or PowerPoint documents when creating PDFs and turn on OCR text recognition when scanning. A PDF is only as accessible as its source file.

- If you link to external websites, consider whether those sites are accessible.

- Provide captions and/or a transcript for all audio/ video materials that you create. For more information on how to make captions in YouTube, see our Quick Guide on this subject at https://spsfaculty.commons.gc.cuny.edu/quick-guides/

In regard to the last point about multimedia, please consider that if you start with a script (which is a good practice), you can more easily produce captions or a transcript! This consideration should be part of your initial process of making multimedia rather than an afterthought or follow-up task.

In Blackboard

- Use descriptive names for files you upload so that screen readers can easily identify them.

- Avoid using colored fonts to enhance meaning as much as possible. Keep the format simple and avoid patterns in the background.

- When designing the left navigation menu in your course site, set the menu style to text—not buttons—and maintain a high contrast between the text and the background color. (You can change these settings on the Control Panel in Blackboard: click “Customization,” then “Teaching Style.”)

- Include Alt Text for all images. When adding an image in your Blackboard site, the Alt Text option will be provided in the pop-up window.

- Enter a “Title” when creating hyperlinks; this will be read by a screen reader. Create meaningful link names that describe the link’s function without the context of other on-screen text (i.e., don’t name the link “click here” or simply use the html address).

Things to Think About:

- Are there any indications from your student course evaluations or from what you have observed about student performance on specific assignments that a substantial subset of students are struggling with understanding course concepts or finding it difficult to accomplish any course tasks in the time allotted?

- Are there any accessibility issues in your course that are already obvious to you? For example, do you ever use any videos in your class that do not contain captions or are accompanied by a transcript?

Things to Do:

- Run a section of your course reading material through a readability index and consider the results.

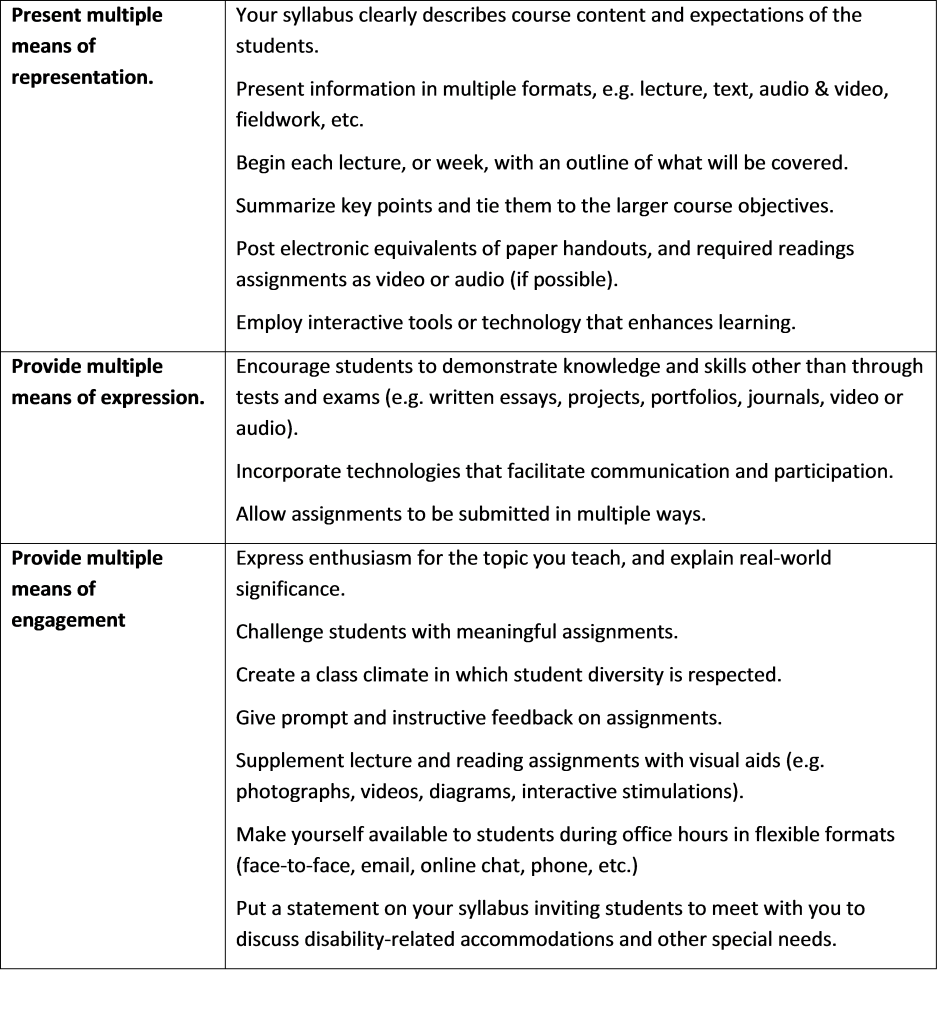

- Consider the Diversity of Learners in Higher Education—check your course for the following points and how you might achieve these:

Accessibility and Universal Design References

“Accessibility Best Practices for eTeaching.” Teaching and Learning Collaborative. The George Washington University. http://info.uwe.ac.uk/online/Blackboard/staff/guides/accessibleContent.asp (accessed April 20, 2015).

SPS Faculty Community Quick Guides on Accessibility and Universal Design in Learning, https://spsfaculty.commons.gc.cuny.edu/accessibility/

Buffalo State SUNY Instructional Design blog: http://ir.buffalostate.edu/microsoft-office.html (accessed April 20, 2015).

Columbia CATS 11-07-2014 AT Seminar Part 3 of 7, Part 4 of 7: http://catsweb.cuny.edu/?page_id=1418 (accessed April 20, 2015).

How to create accessible PDFs, Excel Workbooks, PowerPoint presentations, and Word documents: https://support.office.com/en-us/article/Create-accessible-PDFs-064625e0-56ea-4e16-ad71-3aa33bb4b7ed (accessed April 20, 2015).

Kearns, Lona R; Barbara A. Frey; Gabriel McMorland (2013). “Designing Online Courses for Screen Reader Users.” Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 17.3.

Other References

Some of this material has been adapted from Ko, S. S., & Rossen, S. (2010). Teaching online: A practical guide (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.